Written by Brandon Okey. Mina Draskovic, B.Psy., reviewed this content for accuracy.

The disease model of addiction views addiction as a chronic, relapsing brain disease involving compulsive substance use and loss of control.

While the disease model sees addiction as a result of fundamental neurobiological changes that require medical treatment, many argue that it excuses personal responsibility and oversimplifies the complex nature of addiction.

Regardless of the addiction model, people need help, support, and treatment to overcome addiction.

Our drug and alcohol rehab center offers medical treatment and counseling and gives you the care you need to transform your life. If you or a loved one is struggling with addiction, contact Ardu today and learn about our comprehensive residential therapy and aftercare services.

The disease model of addiction identifies addiction as a disease with biological, genetic, and environmental sources of origin. In many ways, it is similar to other diseases such as diabetes or cancer.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) found “evidence of tissue malfunction in the brains of those with addiction, and in the hearts of people with heart disease.”

According to this model, addiction is not as simple as moral failing or a lack of self-control. The disease model is sometimes referred to as the brain disease model of addiction. They both conceptualize addiction as a chronic disease with deep physiological roots. Controversially, this view has been critiqued for dismissing the agency of individuals and moral responsibility.

We’ll get to that later. First, let’s examine some key points of the disease model of addiction.

Relapse is an unavoidable part of recovery for many battling addiction. Our evidence-based relapse prevention treatment aids in identifying triggers, developing coping strategies, and building a supportive community to minimize the occurrence of relapses.

In many ways, addiction is considered a disease.

Supporters of the disease model argue that it gives a scientific explanation for addiction and, more importantly, reduces the stigma that addiction is a personality flaw or moral weakness.

When addiction is framed as a disease, it helps reduce blame and challenge the notion that willpower alone should override biological drivers of behavior. It offers hope for people with substance use disorder that medical science can develop treatments to target the underlying biological roots of addiction.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, only 6.8% of those in need of addiction treatment end up seeking it. Be one of the lucky ones who turned their lives around by starting your recovery journey at Ardu.

Our drug rehab center provides a compassionate and supportive environment to help you achieve long-lasting recovery from drug addiction. Our alcohol rehab center offers personalized support and evidence-based treatment to help you overcome alcohol dependence.

The disease model of addiction has evolved over the past 200 years as a scientific understanding of the underlying causes of habitual substance use. In the early 1800s, addiction started to emerge as a medical issue that required treatment rather than ridicule and criminal punishment. Physician Benjamin Rush was one of the first to argue that alcoholism stemmed from a physiological disease, proposing a “stimulus treatment” to cure it.

In the late 1800s, the American Association for the Cure of Inebriety pushed for medical care for alcohol and drug addiction rather than moral approaches. They classified addiction as a disease that needs clinical treatment, contrary to pre-existing beliefs.

In the early 20th century, research started to point to enduring chemical imbalances that make recovery difficult for alcohol addiction even after detox. This supported the existence of biological roots and the need for active support and care, similar to other chronic illnesses. Towards the end of the 20th century, addiction was seen as a loss of self-control due to biological, psychological, and societal factors.

Modern neuroscience research since the 1980s has confirmed substance-induced changes in motivation and reward pathways that drive loss of control and push people into addiction. This increase in scientific evidence cemented addiction as a type of brain disorder.

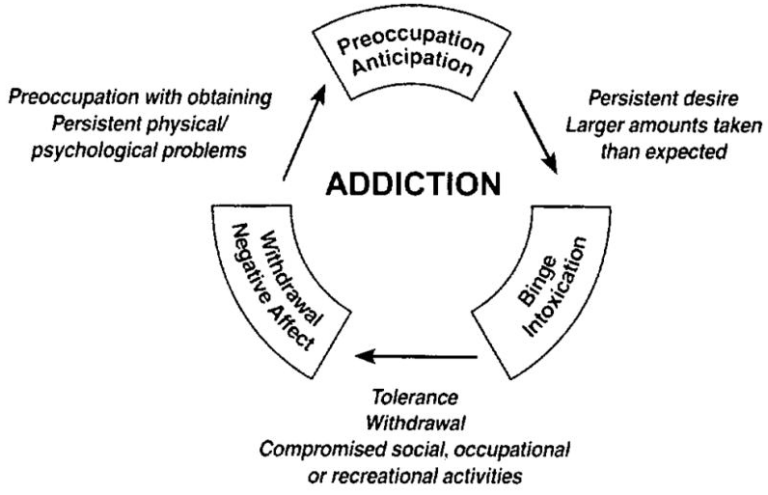

At the core of the brain disease model is the idea that addiction alters brain function and drives compulsive, problematic behaviors. Addictive substances chemically hijack the brain’s communication pathways, leading to changes in structure and function that persist even after substance use stops.

Koob and Simon review major scientific advances over the past 40 years in understanding the neurological and biological mechanisms of addiction. Substantial evidence reveals that the foundations of addiction lie in the biological disruption of neurotransmitters, neural networks, genetics, and molecular signaling cascades.

Let’s break down the major biochemical changes in the brains of people with alcohol addiction.

The disease model posits that addiction is caused by a dysfunction in important brain systems called neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers released by neurons to communicate signals to neighboring cells across synapses.

Addictive substances hijack the activity of key neurotransmitter systems involved in the regulation of mood, reward, motivation, learning, and behavioral control. When these critical communication pathways are disrupted, people spiral into compulsive intoxication and lose control over substance use, which leads to addictive behaviors.

Here are the key neurotransmitters affected by drug and alcohol addiction:

Alcohol, nicotine, opioids, and other addictive drugs flood the neural synapses with abnormally high levels of dopamine and other neurochemicals associated with pleasure and motivation. Banerjee reveals that alcohol, for example, hijacks the brain’s reward and stress pathways by altering neurotransmitter activity, driving addictive behaviors, and eventually leading to alcoholism.

This leads to a counter-adaptation—your brain starts producing less of its natural dopamine and becomes increasingly dependent on a given drug to avoid distressing states of withdrawal. Over time, this leads to a phenomenon called “reward deficiency syndrome.”

The “reward deficiency syndrome” (RDS) attempts to explain a spectrum of addictive, compulsive, and impulsive behaviors rooted in the neurochemical changes of reward circuitry. A 2022 study suggests that neurotransmitter signaling deficiencies in the brain’s natural reward cascade lead to abnormal behaviors, highlighting the importance of dopamine in addiction.

Chen, et. al. explain that “dopamine (DA) is considered to be critical in drug addiction due to reward mechanisms in the midbrain.” In the brains of addicts, dopamine signaling drops so low that they feel unable to experience motivation or joy without the drug on board.

The way addiction sabotages your brain’s mood and motivation pathways is clear proof of addiction as an invasive disease.

If you’re struggling with addiction, the first important step in your recovery is detox. You need to get rid of the harmful substances in your body in order to start the recovery process At Ardu, we offer both drug detox and alcohol detox programs supported by medical professionals.

Addiction triggers lasting changes to neurons at the molecular level. Addictive drugs disrupt the molecular signaling inside your brain cells that regulates how neurons communicate, influence each other’s activity, and create functional circuits.

Your neurons are now reprogrammed and forced to prioritize addiction-related circuits. Research suggests that addiction can make neurons more sensitive, sprout new dendrite branches, and rearrange wiring diagrams. Areas that govern motivation, learning, and behavioral control reshape over time under the influence of addiction.

Things get even worse when you stop using because those changes persist through abstinence. Your brain’s transmission lines are now rewired to seek more drugs to keep the addiction alive. Despite your brain’s neuroplasticity and ability to recover, addiction often makes it seem impossible to revert to healthy functioning.

Addiction certainly demonstrates many of the characteristics of chronic disease and significantly affects the brain at a cellular level.

Read more about what happens to your brain when you stop drinking.

We’ve seen the chaos that addictive substances can unleash from a cellular level. Did you know that the abuse of drugs and alcohol abuse can actually change the structure and function of your brain?

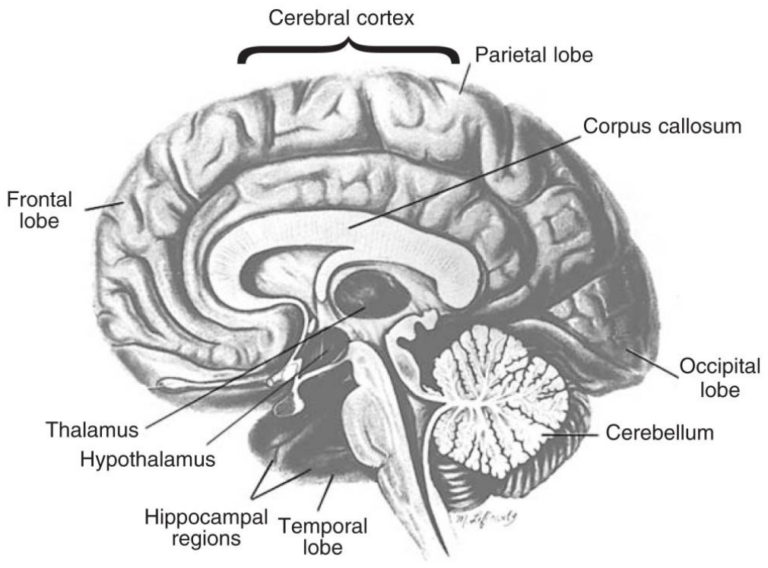

Your brain does physically shrink as you get older, but addiction can exacerbate this shrinkage. According to research, “heavy drinkers had significantly shrunken frontal lobes compared with abstainers.” A 2022 study found that “alcohol intake is negatively associated with global brain volume measures, regional gray matter volumes, and white matter microstructure.”

MRI scans by Zahr, et. al. reveal shrunken prefrontal cortices and cerebellums in alcoholic patients. These are critical areas that govern planning and movement. Alcohol-related prefrontal cortex erosion helps explain the decrease in behavioral control. Cerebellar deficits make smooth motion challenging during intoxication. Stimulants such as cocaine and meth also gnaw away at the gray matter in the areas that control cognition.

Mackey and Paulus reveal that cocaine users lose up to 11% of gray matter in frontal regions compared to non-users. The more time spent using it, the more significant the erosion. Chinese researchers found that chronic methamphetamine use was linked to cortical thickening in bilateral superior frontal gyri—a key player in self-awareness, emotional restraint, decision-making, and cognitive control. The longer someone uses meth, the more gray matter and cortical thickness are lost in the lingual and pericalcarine regions, parts of the brain that are critical for visual discrimination.

Years of heavy substance use can shrink your brain and kill your brain cells. These adverse effects cause progressive cognitive impairments, such as memory problems, impaired judgment, and difficulties with coordination and decision-making. If you are noticing signs of addiction in yourself or a loved one, request an appointment with Ardu today and start your recovery journey.

Genetic factors also provide significant biochemical evidence that supports the disease model of addiction. Genes directly impact an individual’s protein function, neurological development, and neurotransmitter signaling patterns.

A 2012 genetic study showed that genetic factors contribute significantly to the development of addictions, including substance use disorder (SUD) and gambling.

Here’s where some of the strongest addiction disease model evidence comes from:

The way addiction affects the genome and neuronal structure may be definitive proof of its disease directive. On the other hand, the disease model of addiction often faces criticism for diminishing the importance of taking responsibility for personal choices.

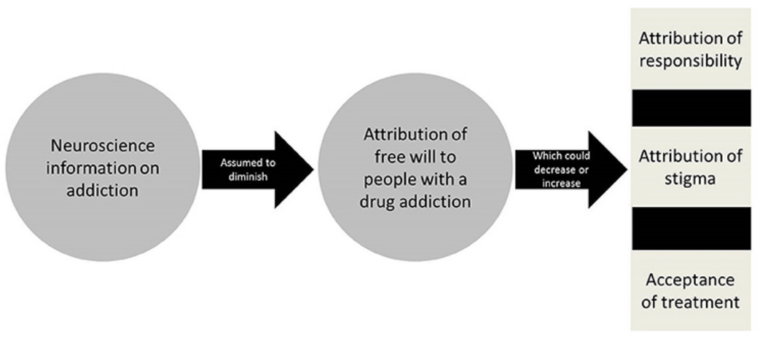

Despite strong evidence that reveals biological disruptions at the base of uncontrolled substance use, many believe that addiction cannot be solely attributed to biology. Critics of the disease model of addiction claim that it relinquishes people of personal responsibility, even though they willfully chose to partake

Hammer, et. al. claim that:

Many argue that framing addiction as a disease will enhance therapeutic outcomes and allay moral stigma. We conclude that it is not necessary, and may be harmful, to frame addiction as a disease.

Here are several reasons critics reject the brain disease model of addiction:

Additional criticisms of the concept of addiction as a brain disease include the failure of this model to identify genetic aberrations or brain abnormalities that consistently apply to persons with addiction and the failure to explain the many instances in which recovery occurs without treatment. (Volkow, et. al.)

While risky neurobiological changes occur with prolonged use, critics fear that conferring brain disease status may go too far in dismissing personal responsibility, contextual drivers, and self-efficacy beliefs that research shows can determine outcomes.

It can be difficult to recognize and acknowledge the fact that you or a loved one may be struggling with addiction. Ardu Recovery Center offers a structured and supportive environment where you can receive medical care, counseling, and therapy to overcome your addiction and regain control of your life.

We tailor treatment plans to suit your unique needs and circumstances. Ardu offers many types of treatment, including dialectical behavior therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and exercise therapy. Whether you’re dealing with an addiction to drugs or alcohol, you will find compassionate, skilled professionals who can help you on your journey to recovery.

Ardu Recovery Center provides the perfect healing environment for those struggling with addiction. Our modern medical facilities in Provo, Utah, deliver cutting-edge, evidence-based care—from detox and therapy to aftercare planning.

We help you through opioid detox and use approved medication to decrease the effects of withdrawal symptoms. Once the detox process is over, our opioid addiction treatment program will support you through continued recovery. If you or a loved one are struggling with heroin addiction, our heroin detox program provides comprehensive care and support to help achieve lasting recovery.

We also offer detox services for the following non-prescription and prescription opioids:

Our comprehensive prescription drug addiction treatment program includes counseling and behavioral therapy to help address underlying issues that contribute to addiction, and ultimately support long-term recovery.

At Ardu, we have highly-trained personnel who specialize in assessing and treating potential medical complications of stimulant use, including addiction to cocaine. We provide detox services for the following stimulants:

All of our personalized plans implement both traditional and alternative treatments to nurture the foundations for long-term well-being. With compassion and expertise, we empower you to overcome addiction, reclaim health, and rewrite your story.

Contact Ardu Recovery Center online or via phone (801-810-1234). We will work with you to find a recovery path that works for you during the detox process and beyond. Contact us to learn more about our rehabilitation programs and breathtaking Provo-based community.

Brandon Okey is the co-founder of Ardu Recovery Center and is dedicated to empowering people on their journey to sobriety.

On the positive side, the disease model of addiction could destigmatize the condition, emphasizing biological underpinnings rather than moral failings. It acknowledges genetic susceptibilities and brain chemistry, shifting attitudes toward addiction, and promoting empathy.

On the other hand, critics argue that it oversimplifies a complex issue, ignoring social and environmental factors. While the disease model supports medical interventions, some question its efficacy in addressing the social dimensions of addiction.

It’s important to strike a balance between acknowledging biological vulnerabilities and considering the broader context is vital for a comprehensive understanding of addiction.

Several models of addiction attempt to explain it:

The disease model sees addiction as a chronic brain disorder. Psychological models focus on mental processes. The moral model of addiction attributes substance abuse to personal flaws or moral shortcomings. Social models emphasize environmental factors, while biopsychosocial models integrate all of them into one.

The Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) disease model perceives alcoholism as an incurable illness, emphasizing the interplay of chronic brain changes and genetic susceptibilities. Within this framework, people in AA regard their struggle with alcoholism as a lifelong battle against a biological predisposition to addiction. AA’s model blends the biological basis of addiction with a supportive community, recognizing the complex interplay between genetics and social interaction in the journey to recovery.

Since AA aligns with the broader understanding of addiction as a chronic brain disorder, the emphasis on abstinence in AA stems from the belief that moderation is not a viable option. This approach, rooted in the disease model, underscores the need for ongoing support, acknowledging the challenges posed by the enduring nature of addiction.

The syndrome model treats substances or behaviors that share common characteristics. Instead of painting addiction with a broad brush, this model suggests looking for patterns and similarities across different addictive elements. It’s a nuanced way of understanding addiction, acknowledging that it’s not a uniform experience.

The syndrome model nudges us to explore the connections between different addictive behaviors, creating a more detailed and intricate picture of addiction as a shared set of traits rather than a singular, isolated condition.

The consequences of the disease model include a potential oversimplification of addiction, emphasizing the need for a holistic understanding that considers both the biological and sociocultural dimensions of addiction.

Beyond destigmatization, the disease model of addiction facilitates medical interventions by prioritizing the biological basis of addiction. A potential drawback may be an oversight of critical psychosocial elements. Solely concentrating on biology may sideline the influences of social interactions, environmental factors, and genetic susceptibilities.

It’s important to strike a balance and acknowledge biological roots without neglecting the broader context for a comprehensive approach.

Some people assert that addiction doesn’t neatly fit into the disease category. The argument stems from insufficient evidence to exclusively categorize it as a chronic brain disorder. This isn’t a one-size-fits-all scenario; addiction is a complex puzzle. It’s not just about human brain chemistry; we need to consider the intricate interplay of social interactions and environmental factors. Slapping the “disease” label on addiction might oversimplify the situation and cause us to miss the broader picture.

NIDA – Drug Abuse and Addiction: One of America’s Most Challenging Public Health Problems. (n.d.). https://web.archive.org/web/20130219201821/http://archives.drugabuse.gov/about/welcome/aboutdrugabuse/chronicdisease/

Addiction Treatment | National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2023, September 27). National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://nida.nih.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/treatment/addiction-treatment

Koob, G. F., & J. Simon, D. E. (2008). The Neurobiology of Addiction: Where We Have Been and Where We Are Going. Journal of Drug Issues, 39(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260903900110

Banerjee, N. (2014). Neurotransmitters in alcoholism: A review of neurobiological and genetic studies. Indian Journal of Human Genetics, 20(1), 20-31. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-6866.132750

Blum, K., McLaughlin, T., Bowirrat, A., Modestino, E. J., Baron, D., Gomez, L. L., Ceccanti, M., Braverman, E. R., Thanos, P. K., Cadet, J. L., Elman, I., Badgaiyan, R. D., Jalali, R., Green, R., Simpatico, T. A., Gupta, A., & Gold, M. S. (2022). Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS) Surprisingly Is Evolutionary and Found Everywhere: Is It “Blowin’ in the Wind”? Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12020321

Chen, W., Nong, Z., Li, Y., Huang, J., Chen, C., & Huang, L. (2017, July 21). Role of Dopamine Signaling in Drug Addiction. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568026617666170504100642

Nestler, E. J. (2013). Cellular basis of memory for addiction. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(4), 431-443. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.4/enestler

Kubota, M., Nakazaki, S., Hirai, S., Saeki, N., Yamaura, A., & Kusaka, T. (2001, July 1). Alcohol consumption and frontal lobe shrinkage: study of 1432 non-alcoholic subjects. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.71.1.104

Daviet, R., Aydogan, G., Jagannathan, K., Spilka, N., Koellinger, P., Kranzler, H. R., Nave, G., & Wetherill, R. R. (2022, March 4). Associations between alcohol consumption and gray and white matter volumes in the UK Biobank. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28735-5

Zahr, N. M., & Pfefferbaum, A. (2017). Alcohol’s Effects on the Brain: Neuroimaging Results in Humans and Animal Models. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38(2), 183-206. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5513685/

Mackey, S., & Paulus, M. (2013). Are there Volumetric Brain Differences Associated with the Use of Cocaine and Amphetamine-Type Stimulants? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(3), 300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.12.003

Nie, L., Zhao, Z., Wen, X., Luo, W., Ju, T., Ren, A., Wu, B., & Li, J. (2020). Gray-matter structure in long-term abstinent methamphetamine users. BMC Psychiatry, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02567-3

Ducci, F., & Goldman, D. (2012). The Genetic Basis of Addictive Disorders. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 35(2), 495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.010

Verhulst, B., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2015). The heritability of alcohol use disorders: A meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychological Medicine, 45(5), 1061. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714002165

Kaplan, G., Xu, H., Abreu, K., & Feng, J. (2022). DNA Epigenetics in Addiction Susceptibility. Frontiers in Genetics, 13, 806685. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.806685

Hammer, R., Dingel, M., Ostergren, J., Partridge, B., McCormick, J., & Koenig, B. A. (2013). Addiction: Current Criticism of the Brain Disease Paradigm. AJOB Neuroscience, 4(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2013.796328

Racine E, Sattler S, Escande A. Free Will and the Brain Disease Model of Addiction: The Not So Seductive Allure of Neuroscience and Its Modest Impact on the Attribution of Free Will to People with an Addiction. Front Psychol. 2017 Nov 1;8:1850. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01850. PMID: 29163257; PMCID: PMC5672554.

VOHS, K. D., & BAUMEISTER, R. F. (2009). Addiction and free will. Addiction Research & Theory, 17(3), 231. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350802567103

Volkow, N. D., Koob, G. F., & McLellan, A. T. (2015). Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(4), 363. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1511480

What are the types of illegal drugs?

How long does alcohol detox take?

What detox signs is your body showing?

What drugs cause severe kidney damage?

What happens to your liver when you stop drinking?

What are the signs of heroin addiction?

What are the alcoholics statistics in the United States?